An essay – by Mirianna la Grasta

The Great War, best known as the First World War, was an unprecedented conflict in terms of length, weapons and casualties. It started in 1914 and ended in November 1918 leaving the United Kingdom triumphant on the one hand, but profoundly wounded on the other. As a deadly war went on the government tried to control every single channel of communication through propaganda and censorship, and allowed just a few correspondents to join the forces in France (Carruthers, 2011:50).

The same Lloyd George, who during the war was first Chancellor of the Exchequer, then Minister of Munitions, secretary of state for war and finally Prime Minister in December 1916, described the conflict as “horrible” and “beyond human nature to bear” (BBC, 2014; Fussell, 2013:189,190). He added that people couldn’t know the truth about war because they would have insisted for it to be stopped (Fussell, 2013:190). This is the reason why during the Great War “more deliberate lies were told than in any other period of history, and the whole apparatus of the state went into action to suppress the truth” (Knightley, 1989:80).

Then, two separate worlds developed.

The first one was the world of “make believe” at home. Journalists began to serve the state’s interests by following a strict code of censorship and rules. Whether they were in Britain or in France the only way they could access the news was reading the Press Bureau’s communiqués, and even when they had some sort of access to information they practiced self-censorship and fabrication of atrocity stories, adding legitimacy to what the government was doing, ultimately contributing to “the great conspiracy, the deliberate lies and the suppression of truth” (Farrar, 1998:7,14,73).

Through their work, English poets initially supported the conflict by celebrating the heroic struggle for the right and the Englishmen’s sacrifice for an ideal of patriotism and country (Lehmann, 1981:8). Their mood, however, darkened as the war went on and a second reality, or world, developed. Especially after the Battle of the Somme (1916), in which Britain lost 410,000 men, soldier-poets realized the conflict was just an endless and pointless carnage, full of suffering and horror (Lehmann, 1981:9). As their dreams crumbled, their poetic patriotism was replaced by despair, disillusionment and above all frustration, because it was almost impossible to make their families understand what was happening on the other side of the Channel (Ibid.).

No surprise then if Virginia Woolf acclaimed Siegfried Sassoon’s poetry for its “terrible pictures which lie behind the colourless phrases of the newspapers” (Woolf, 1918). As Lonsdale (2016) explains:

“War poets react with violent imagery to newspaper coverage of the First World War. Their poetry, a documentary literature of ‘correction’ in opposition to the perceived lies, platitudes and lack of dissent against government policy in the press.” (Lonsdale, 2016:47)

In this essay I will argue that the English poetry of the Great War belonging to the late period, 1916-1918, can be considered as a more accurate and honest representation of the conflict if compared to the articles written by war correspondents.

In his fictionalised Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930), war poet Siegfried Sassoon summarises what his reaction to the “colourless phrases of newspapers” was: he speaks about one author from daily paper as “some amiable man who [in writing his article] had apparently mistaken the war for a football match between England and Germany” (Sassoon, 1989:185,186). He goes on describing the conflict as a “camouflage war” manufactured by the press (Ibid.). In the late poetry of the Great War Sassoon represents the first proper stage of consciousness: his consciousness of the political errors and journalism’s insincerities translates into protest-poetry through the recreation of physical horrors, anger, satire and sardonic distancing (Silkin, 1979:27).

Like Sassoon, also Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg – both soldier-poets – felt that their sacrifices were being misrepresented and trivialised by the English press. Having suffered in the French trenches they started creating a literature of correction to the falsities spread by the newspapers: what pushed them to compose violent, harsh and shocking poetry was the idea that the Great War’s carnage had been presented as a football match between nations (Lonsdale, 2016:58,59).

As a result, apart from being “Romance”, the soldier-poets’ literature of correction became nothing but “reporting” (Eliot, 1919 in Lonsdale, 2016:59):

The place was rotten with dead; green clumsy legs

High-booted, sprawled and grovelled along the saps

And trunks, face downward, in the sucking mud,

Wallowed like trodden sand-bags loosely filled;

And naked sodden buttocks, mats of hair,

Bulged, clotted heads slept in the plastering slime.

(lines 7-12, first stanza, “Counter-Attack” by Siegfried Sassoon)

This extract is part of one of Sassoon’s more realistic and descriptive pieces, “Counter-Attack”. The lines are particularly effective as they help the writer to achieve an effect of protest, by the mounting horror of its details (Lehmann, 1981:40,41). The poet, here, is describing the consequences of a failed counter-attack on the German line: the attack has been so deadly that Sassoon dedicates six entire lines to the description of the corpses in order to shock the reader and to give him an exclusive, real and horrific story of death that he would not be able to find in newspapers. His poems, indeed, were “deliberately written to disturb complacency” (Lehmann, 1981:39).

While Sassoon wanted to shock the English public to the “ghastly suffering” that was behind the cold communiqués, Owen represents a second state of consciousness in the late poetry of the Great War: compassion (Lehmann, 1981:55; Silkin, 1979:27). Owen’s scope was to communicate a strong feeling: “My subject is war, and the pity of war,” he said (Lehmann, 1981:55).

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

(Second and third stanzas, “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen)

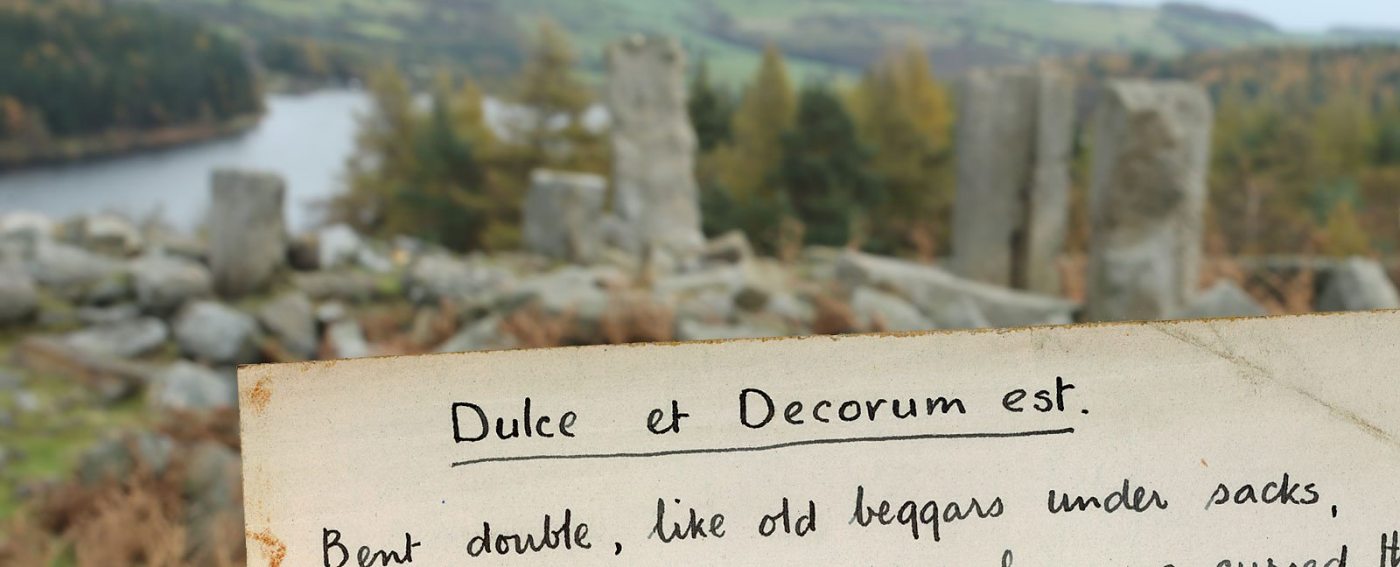

Despite being a poem, Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” (1917) narrates a gas attack and its consequences better than any other journalistic account of the time. The second stanza, in particular, highlights the poet’s “I” through expressions like “I saw him”, “my dreams”, “my sight”, “plunges at me”, revealing that the author is witnessing the scene for real as a correspondent would do. In the whole poem his “documentary attention to detail”, as Lonsdale (2016:61) calls it, the use of the direct quote – “Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!” -, the numerous descriptions – “Bent double, like old beggars under sacks”, “Men marched asleep… All went lame; all blind; Drunk with fatigue”, “thick green light” -, the use of common visual verbs – “we cursed” and the enumeration “plunges… guttering, choking, drowning” – make the reader understand that Owen goes beyond poetry and achieves reportage.

Wilfred Owen’s poems, in fact, can be read as manifestos: they are “truthful reports” on what was happening at the Front, so truthful that they have been considered far deeper in their disclosure of reality than anything the war correspondents could or would write (Lehmann, 1981:55).

At the same time, newspapers such as the Times downplayed the effects of gas warfare in their reports. Writing about the Battle of Ypres on April 30, 1915 a correspondent says:

“The wind, however, was strong and dissipated the fumes quickly, our troops did not suffer seriously from their noxious effect… On Saturday…[the soldiers found] the German trenches rendered invisible by a wall of greenish-yellow… which was bearing down on them on the breeze.” (Times, 3 May 1915)

Clearly, the report is minimizing the serious noxious effects of the fumes, which, by the end of the war, will cause nearly 186,000 casualties in the British Expeditionary Force. Moreover, rather than talking about the effect of the gas on the British army, the journalist focuses on the fact that the enemies are the ones who suffer the most from this kind of attack, describing them with the words “[they] were so affected … that they could not advance” (Times, 3 May 1915). By doing this, the reporter is not only avoiding talking about the severe poisoning of the British men, but is also instilling the hope of victory in the minds of the readers.

Owen might appear as one of the most truthful and authentic voices of compassion in English poetry. Isaac Rosenberg, however, not only passed Owen by writing a more intimate poetry, but also reached the last stage of consciousness in the late English poetry of the First World War (Silkin, 1979:27,28). Even though he hated the war, his work was neither a poetry of protest, like Sasson’s, nor a poetry of compassion aimed at striking the non-combatants and the politicians, as Owen’s (Lehmann, 1981:119):

The wheels lurched over sprawled dead

But pained them not, though their bones crunched,

Their shut mouths made no moan,

[…]

Earth has waited for them

All the time of their growth

Fretting for their decay:

Now she has them at last!

[…]

A man’s brains splattered on

A stretcher-bearer’s face;

His shook shoulders slipped their load,

But when they bent to look again

The drowning soul was sunk too deep

For human tenderness.

[…]

Here is one not long dead;

His dark hearing caught our far wheels,

And the choked soul stretched weak hands

[…]

Will they come? Will they ever come?

[…]

We heard his weak scream,

We heard his very last sound,

And our wheels grazed his dead face.

(“Dead Man’s Dump” by Isaac Rosenberg)

By reading these lines from the “Dead Man’s Dump” it is possible to understand that the aim of Rosenberg’s poetry is to show the most appalling side of life as he experienced it at the Front (Lehmann, 1981:119). By describing the deadly reality and the agony of war, Rosenberg achieves that journalistic authority that correspondents had lost.

To a certain extent also British war correspondents wrote dramatic stories, but these were completely different from the ones narrated by Rosenberg: they were, in fact, false atrocity stories about the Germans, designed as propaganda pieces to raise both the people’s heroic sentiment and their anger against the enemy (Knightley, 87-111). By contrast, in the “Dead Man’s Dump”, Isaac Rosenberg sees the casualties of the battle, English and German soldiers, as equal: the war, indeed, was atrocious for everyone. These strong and vivid images of death – the multitude of corpses in a desert piece of land and this lonely carriage passing over them – would have provoked revulsion and surprise in the non-combatants, who were not used to the truthful accounts of the war and were not aware of what was going on at the Front.

The poetic imagery we found in these three works is violent because it reflects Sassoon, Owen and Rosenberg’s experience of a violent war. This can be considered their reaction to the lack of eyewitness reporting during the war by the news media (Lonsdale, 2016:49). As we have seen, the poet was the protagonist of the war poetry produced between 1916 and 1918. Unlike war correspondents, “who spent much of their time in comfortable chateaux miles from the front line”, the poet was actually at the Front, living the war and suffering with his fellow soldiers (Lonsdale, 2016:49). The poet will be, thus, the protagonist and the eyewitness of a war that will be remembered and studied in the following years and that journalists failed to report.

If, on the one hand, poets truly became more honest chronicles of the war than war correspondents, this does not mean that they praised what their poetry was becoming. In his Retort Discourteous imagist poet Richard Aldington criticises the fact that during this historical period people expected poetry to tell them some piece of news, “and indeed poetry has no news to tell anyone,” he said, explaining that he did not want his poetry to be read curiously and quickly as one reads a newspaper column (Aldington, 1915:4). His reaction can be explained by Bourdieu’s concept of the field of cultural production: he was trying to delimit the poetic field and to restore the borders threatened by journalism, its lies and self-censorship. According to Aldington, during the First World War the unpaid war poet who told the truth occupied a superior position within the cultural field than the paid and lying journalist, who followed the government’s will (Lonsdale, 2016:49).

To sum up, the English poetic production that goes from 1916 to 1918 can certainly be praised as a more honest and truthful account of the Great War than the one provided by war correspondents. Despite lacking the “objectivity and impartiality” value, on which contemporary journalism relies, and giving space to the poet’s “I”, the poems written by Sassoon, Owen, Rosenberg and many others – whom I did not take into consideration for a close analysis, but that are worth mentioning: Graves, Thomas, Blunden, Gurney, Harvey, etc., – depicted terrible but truthful pictures of the conflict, something that journalism failed to achieve as it was subjected to censorship and laws.

Nevertheless, the assumption by many scholars that war correspondents were not honest chronicles of the Great War needs further research. When criticizing war correspondents for the lack of true pieces of journalism, scholars only refer to that group of journalists who covered the combats on the Western Front. The term “Great War”, however, does not just refer to the military combats, but also to the daily problems that non-combatants were facing in Britain. And by extension the term “war correspondents” may refer to those journalists covering internal affairs during the war. In “Roast Seagull and other Quaint Bird Dishes” (2015), Sarah Lonsdale makes an argument for all the ignored sections of newspapers at the time, which offered advice on how to cope with the tough circumstances caused by the war. Even if civilians were not aware of the slaughter happening in France, they were living another side of the war, which, contrary to the military one, was always narrated, in the form of “lifestyle” pieces, by journalists.

Bibliography

Aldington, R., 1915, “The Retort Discorteous”, Little Review, vol. 2, no. 4, p. 4.

“A Match for German Chemicals”, 3 May 1915, Times.

BBC – History, 2014, David Lloyd George (1863-1945) [Online] Available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/george_david_lloyd.shtml [Accessed on 26 February 2017]

Boyce, D.G., Curran, J. & Wingate, P. 1978, Newspaper history from the seventeenth century to the present day, Constable, Beverly Hills, Calif;London;.

Carruthers, S. L., 2011. The media at war. 2nd edition ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Engel, M., 1997. Tickle the Public. 2nd edition ed. London: Indigo.

Farrar, M. J., 1998. News from the front. First edition ed. Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Limited.

Fussell, P., 1924-2012 2013;1975;, Great War and modern memory, New edn, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Gardner, F., 2014. BBC. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zs9bwmn [Accessed 12 December 2015].

Greenslade, R., 2014. First world war: how state and press kept the truth off the front page. [Online] Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/jul/27/first-world-war-state-press-reporting [Accessed 8 December 2015].

Knightley, P., 2004. The first casualty. 5th edition ed. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press.

Lehmann, J., 1907 1981, The English poets of the First World War, Thames and Hudson, London. Literature and culture in modern Britain: 1900-1929 / Vol.1, 1993, Longman.

Lonsdale, S. 2015;2014;, “Roast Seagull and other Quaint Bird Dishes: The development of features and “lifestyle” journalism in British newspapers during the First World War”, Journalism Studies, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 800-16.

Lonsdale, S. 2016, The journalist in British fiction and film: guarding the guardians from 1900 to the present, Bloomsbury Academic, London.

Macaulay, R., 1881-1958 2012, Non-combatants and others, General Books, Memphis.

Mathews, J. J., 1957. Reporting the wars. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McLaughlin, G., 2002. The war correspondent. First edition ed. London: Pluto Press.

Owen, W., Stallworthy, J. 2000, The complete poems and fragments: Volume I, The poems, Chatto & Windus, Cambridge, England; London;.

Pugh, T. & Johnson, M.E. 2014, Literary studies: a practical guide, Routledge, London.

Sassoon, S. 1989;1930;, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, Faber and Faber, London.

Sassoon, S. 1983, The war poems of Siegfried Sassoon, Faber and Faber, London.

Silkin, J. 1979, The Penguin book of First World War poetry, Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Winkler, J., 2001. FROM THE ARCHIVES EARLY CORPORATE ESPIONAGE AMID WORLD WAR I CENSORSHIP. Cryptologia, 25(2), pp. 91-94.

Woolf, V. 11 July 1918, “Two Soldier-Poets”, Times Literary Supplement, p. 323.

Leave a comment